The plot of your screenplay is the sequence of events that acts as the backbone of your story, and is driven forward by your protagonist’s motivations and actions. In this article we'll examine the traditional three act structure and five plot points. This is by no means the only approach to plot and story structure, however it is the foundation of nearly all great stories in film and TV, and all beginning screenwriters would do well to master these concepts.

A simple way to approach your screenplay is: CHARACTERS + PLOT = STORY

To better understand how to improve the plot of your screenplay, it’s important to look at the elements that form the foundation of basic story structure.

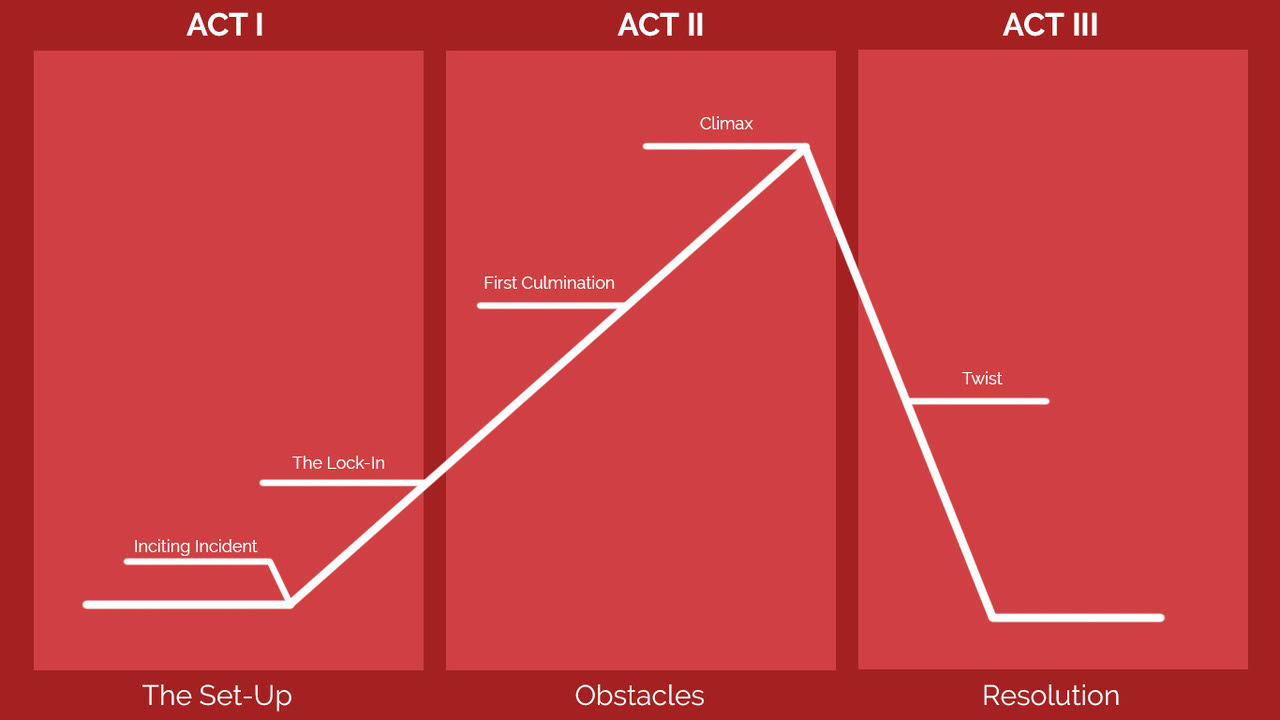

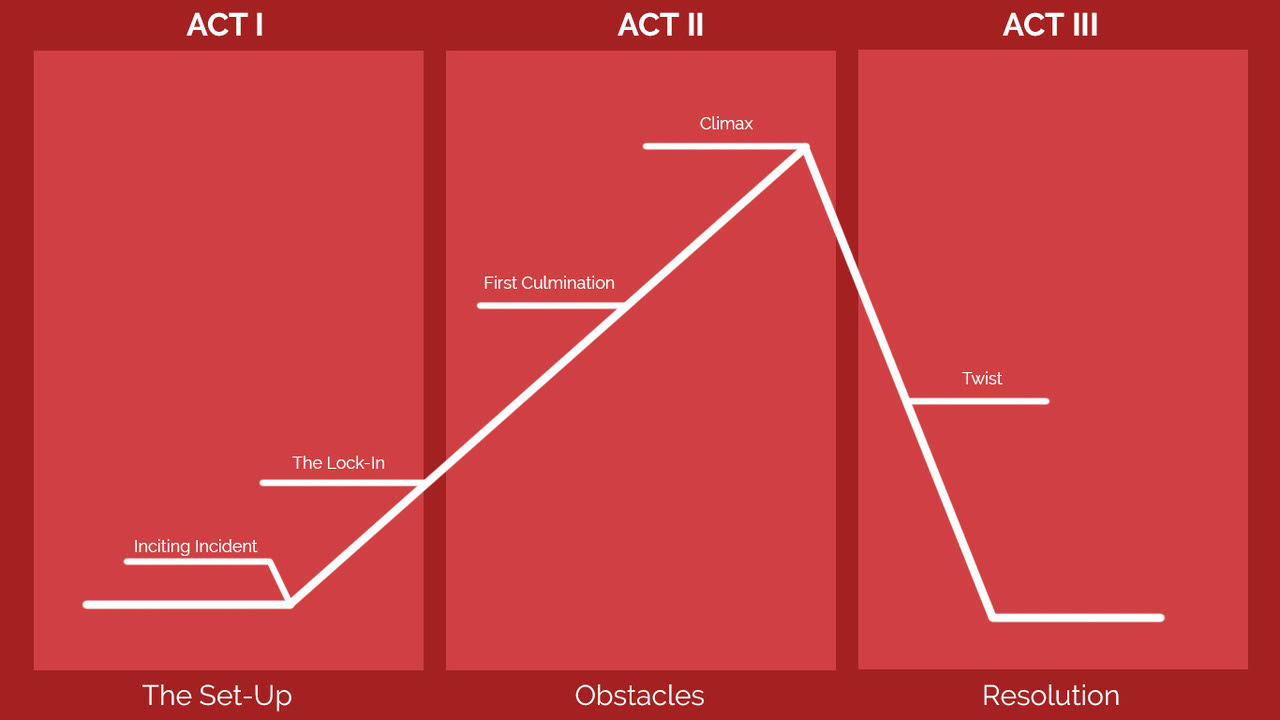

Basic Three Act Structure

Every story has a definitive beginning (Act I), middle (Act II), and end (Act III), and each act serves a specific purpose.

Let’s take a closer look at the primary elements of the three act structure.

The Set Up introduces your setting and characters while establishing the rules of their world, the tone of the story going forward, and the protagonist’s weaknesses and strengths. It hooks both the reader and the characters into the action.

Act II is a series of rising tensions and obstacles that accumulate at the climax of your plot. It’s perhaps the most difficult section of your script. Act II is filled with minor successes and major failures that force a character to evolve in order to conquer their main flaw and face their conflict head on. It’s the heart of your story, so take care of it.

A good exercise in your first or second rewrite is to go back and make sure all the story threads and subplots introduced in Act I connect with the obstacles of Act II.

Act III moves fast and is with precision. The main conflict and subplot collide with a twist or resurgence of a threat, and the character has to use everything they learned in Act II to conquer the final obstacle. The solution is often in contrast with the character’s main flaw. Once the conflict is resolved, there is a new status quo.

—

The Five Plot Points

From the foundation of the three act structure, let’s look closer at the five plot points of a basic story arc.

- Inciting Incident - The introduction of the main conflict that threatens normalcy.

- The Lock In - The protagonist becomes locked in to face the main conflict.

- First Culmination - The midpoint where the character finds a solution that might work.

- Main Culmination - The climax of the screenplay where the peril and magnitude of the conflict seems to overpower the protagonist.

- Twist - The final culmination and change in direction where the plot and subplot collide.

—

The Eight Sequences of the Three Act Structure

Within the framework of the five plot points, a screenplay typically contains eight sequences that hit on similar beats.

ACT ONE

Sequence 1 – Introduce Main Character/Status Quo

Plot Point #1: Inciting Incident/Point of Attack

Sequence 2 – Set Predicament/Establish Main Tension

Plot Point #2: The Lock In

ACT TWO

Sequence 3 – First Obstacle/Raise the Stakes

Sequence 4 – Higher Obstacle

Plot Point #3: First Culmination

Sequence 5 – Subplot/Rising Action

Sequence 6 – Highest obstacle

Plot Point #4: Main Culmination

ACT THREE

Sequence 7 – New Tension

Plot Point #5: Twist

Sequence 8 – Resolution

—

Advanced Structuring

Once you have the fundamentals down, you can begin to look at more advanced modes of structure for inspiration. You can rearrange or reverse the order of events, use other structuring principles, and even discover your own techniques.

One popular story structure technique is explained by writer Dan Harmon's Story Circle. Harmon (creator of Community and Rick & Morty) distilled Christopher Vogler's book, The Writer's Journey, itself an elucidation of Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey, as follows:

- A character is in their comfort zone,

- But they need something.

- They enter into an unfamiliar situation,

- They adapt to it,

- They get what they wanted,

- They pay a heavy price for it,

- Then they return to their familiar situation,

- Having changed.

Some great resources for advanced story structuring can be found on our partner ScreenCraft’s blog:

10 Screenplay Structures that Screenwriters Can Use

Unconventional Story Structures for Screenwriters

The 12 Stages of the Screenwriter’s Journey

The structure of your screenplay is essential to holding your audience's attention. Each scene serves a function of the plot, which is an extension of the leader character(s) goals and arc. Understanding these concepts can help you choose to eliminate unnecessary scenes that might slow your story down and make for a more engaging read.

Kevin Nelson is a writer and director based in New York City, baby. He has written and produced critically acclaimed short films and music videos with incredibly talented artists, worked with anti-human trafficking organizations in Nepal, and would rather be in nature right now. Check out his Coverfly profile, see more madness on Instagram or follow his work on https://www.kevinpatricknelson

For all the latest from Coverfly, be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.